Commerce and industry minister Piyush Goyal’s comments last month that Indian startups were doing very little in the realm of deeptech may have ruffled a few feathers, but it struck a nerve for a reason. Well, by now, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that India is miles behind its more advanced peers like the US and China.

Now, there may be plenty of explanations — — but the hard truth is that India’s deeptech euphoria has been built on shaky grounds. While many of us may agree to disagree (yet again), a major case in point is the Indian startup electric vehicle (EV) ecosystem.

Let’s understand how, but first…

India’s EV Startup Legacy In A SnapshotAbout a decade ago, in 2015, the Indian government rolled out a subsidy plan — the Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of Hybrid and Electric Vehicles (FAME) — for the then-nascent EV sector. The scheme was aimed at promoting hybrid and electric vehicle technologies in India.

The government’s intent around EVs was clear, and the industry eagerly bought into the vision. Consequently, investments and funding started pouring in, and EV startups began to spring up. What sweetened the pot was government subsidies, which fuelled the adoption of two- and three-wheeler EVs. And as the demand rose, more players mushroomed in the sector to cater to a new breed of transportation.

During this time, a large portion of new EV startups were either producing scooters or three-wheelers in the L3 and L5 segments.

As per Vahan data, by 2019, there were a total of around 450 registered EV companies that were selling in India. These included startups like Ather Energy, Euler Motors, Ampere Vehicles, HOP Motors, and Okinawa Autotech, among others.

By 2022, this number increased to more than 560 EV companies, with the likes of Ola Electric, Bounce, EVage Motors, and Omega Seiki joining the race.

From the very look of it, one would feel that the country’s EV startup landscape was on the right track and was ready to take off. While this did happen, traditional automotive giants decided to clutter the space, posing a threat to their younger peers.

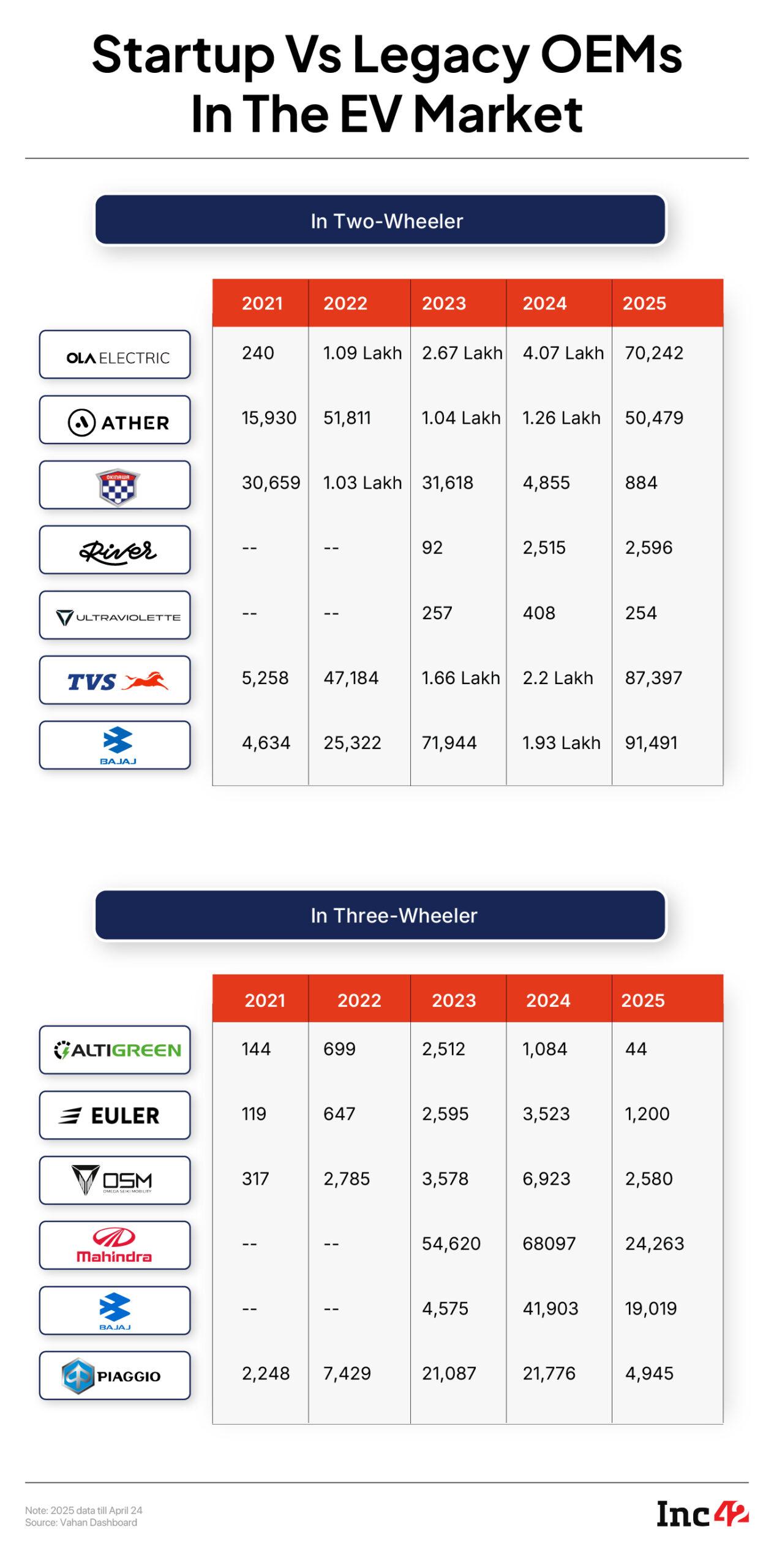

As expected, weak links could not survive and perished. For instance, the likes of Okinawa, Hero Electric, Pure EV, and Jitendra EV, among a dozen others, slowly perished amid the Centre’s crackdown on the usage of Chinese parts. With the rise of legacy players like TVS Motor and Bajaj Auto, the only native EV startup that has been able to stand tall against the headwinds posed by the old titans is Ola Electric.

However, once seen as a strong challenger in the Indian EV space, the Bhavish Aggarwal-led EV maker has started to lose its sheen.

The startup that was once selling more than 30K to 40K EVs a month is now Hero-backed Ather Energy, another native EV manufacturer, has also failed to scale significantly to beat the legacy giants.

But, are EV OEMs doing any better in the commercial space? Not really. Unsurprisingly, players like Bajaj, Mahindra and Piaggio are leading the race consistently, leaving EV startups operating in the commercial three-wheeler space behind.

One may wonder: Why has India’s once-burgeoning EV startup ecosystem lost its momentum? While many may blame the Centre for lowering subsidies and tightening the policy noose for the slow collapse of many native EV OEMs, the truth is far stranger than fiction.

For one, only a few EV natives have been serious about building technology and high-quality products since the onset of the EV wave in the country.

In the presence of hordes of EV players importing the EV tech and the product from China, the Indian market got filled to the brim with cheap-quality, subpar products. This is where legacy players saw a white space and decided to beat natives in their own game with high-quality and reliable EVs.

“Automotive is a very serious business. Anyone can sell a bad product for a short time, but in the long run, the products have to be good,” said Deb Mukherji, automotive veteran and advisor at Anglian Omega Group, adding that long-term disruptions in this line of work can only happen if you are equipped with a solid technology or product or have established robust supply chain and distribution channels.

Meanwhile, today building a brand in this line of work has become or arduous than three or four years ago. Why? The industry has matured, having already navigated through rough patches, wrong routes, and missteps.

Ghost Of The Past: Between 2021-2022, India’s EV dreams were literally on fire, and the trigger was substandard EV products zipping on Indian roads. An increasing number of fire-related incidents, along with other kinds of breakdowns, including the breaking of the front suspension, started dominating headlines across channels.

Such incidents raise a slew of questions on the quality of products being offered to end users. Even after-sales services of many players were not up to the mark.

During this time, apprehensions ran rife that native EV OEMs scrooging on quality, tech or aftersales would either shut down or get acquired.

Ironically, that’s the pulpit the Indian EV sector now stands on. Around mid-last year, .

Since then, the situation has escalated into a full-blown crisis, affecting EV startups not only in the OEM category but also in other segments.

For example, Log9 Materials, a Bengaluru-based battery tech startup, is in crisis due to its technology failure. Similarly, Altigreen Propulsion Labs has failed to raise funds amid dwindling sales. The 2023-launched Orxa Energies has also stopped its production. And let’s not forget about governance issues plaguing Indian startups, which have now started making EV players their collateral damage. Remember how the BluSmart saga unfolded?

So, Is OEM Not A Startup Game?According to Mukherji, Ather Energy is the only player among the existing Indian two-wheeler OEMs that shows promise and can lock horns with Bajaj, TVS, Honda, and Hero.

Recently, Hero MotoCorp-backed Ather filed its RHP with SEBI and is set to become the first new-age tech company to go public in 2025.

While Mukherji believes not many players can beat legacy automotive giants in the long haul, he did not quash the possibility of new and more advanced OEMs breeding from India.

“In India, where EV sales are expected to reach 20 Mn by 2030, even if the automotive giants take 70-80% of the market share, there will still be 20% available for the newcomers, which is a big market still open for the startups,” he said.

Meanwhile, Kunal Khattar, partner, AdvantEdge, an EV-focussed VC, sees a huge scope for startups in categories such as ebuses, etrucks, and etractors.

The Indian EV market has so far been piggybacking on escooters, creating a significant gap in other categories, including bikes.

Khattar sees more startups filling these categories with superior technology. Therefore, he has refrained from concluding if Indian EV startups have lost the OEM game altogether.

Besides, he acknowledges that new-age startups have unique strengths, such as design, speed and agility, while legacy companies enjoy a strong brand name and distribution.

“If startups can build brands with robust distribution (which Ola Electric had the potential to do but failed), they stand a chance against legacy players,” he said.

However, Yatish Rajawat, the founder of the Centre for Innovation in Public Policy, has a different perspective.

He believes OEM is not a startup game. Giving rationale behind his belief, he said that it is a capital-intensive business and only deep-pocketed traditional players have the muscle to pull it off. Plus, transitioning to EVs makes more sense amid the current scheme of things when the government is banning diesel vehicles and increasing ethanol in petrol.

“We must also understand the dynamics of policy — who is getting the policy made and who will get the incentives?” Rajawat said.

He added that the companies benefiting the most from incentives are the ones that are making the bulk.

“Hero, Bajaj, Hyundai, Maruti, and other big players are driving the policies because they have the scale. Newly emerged startups do not have enough sales or revenue to get policy benefits,” said Rajawat.

Not to mention, he said, the startups that tried to scale quickly to show scale started manipulating numbers and policy norms, leading to their early demise.

With OEM Dream Flickering, What’s Next?While many new-age startups have struggled as EV manufacturers, they are finding stronger footing in other parts of the electric mobility value chain — EV infrastructure, financing, and sub-components.

According to Khattar of AdvantEdge, while traditional financing players are struggling to ascertain the residual value of EVs, the likes of Revfin, Alt Mobility, and other EV-first financing businesses are gaining ground.

“Besides, I think EV insurance will slowly see startups emerging. I still do not see a good EV warranty company, which remains a big opportunity. Battery as a service is another opportunity that is just taking off, hence more players will join,” he said.

Meanwhile, Mukherji identified battery management systems (BMS) as a promising space for Indian startups, which currently lacks strong tech players. He also sees great potential in the powertrain segment.

“While a few startups have begun working on powertrains, they are struggling because they do not have good motors and controllers. So motor and controller, I think, are the areas where startups will succeed, and this is a great opportunity,” he said, adding that serious startups may end up getting legacy OEMs on their side, either as clients or parents.

However, a few areas, such as cell manufacturing and EV charging infrastructure, remain more capital-intensive and dependent on building a strong supply chain ecosystem where startups may find it challenging to survive.

Not long ago, the future seemed electric — EVs zipping through Indian cities, no internal combustion engines roaring, guzzling fuel, or spewing particulate matter. But a decade on, the dream of an EV-ready India appears to be flickering on the horizon.

Despite this, India is determined to create a by 2030. Whatever role Indian startups will play to achieve this dream will be fascinating to observe, to say the least.

[Edited By Shishir Parasher]

The post appeared first on .

You may also like

'Ground Zero' Public Review by IANS: Empty theatres, film gets mixed response on opening day

Freddie Flintoff's huge drop in earnings revealed after near-death Top Gear crash

Wagah-Attari border closure leaves several families in limbo

Love eating chicken? Study links regular consumption with gastrointestinal cancers

Karnataka police file FIR over social media post defending Pahalgam terror attack; hunt on for accused